Beatrice Richards leans over the tape and cranes her neck. It’s November 7, 2021, and she’s staked out a spot on the corner of Lafayette and Bedford Avenues in Brooklyn, US, just past the 14 kilometre mark of the New York City Marathon. Her son, Thai, should be along any second.

Beatrice wasn’t always there for Thai. Not like this, at least. She had him when she was 16; by 23 she was working long hours at the post office. As a single mum, Beatrice was determined to make a good life for herself and her son. That meant finishing college, a job, sometimes more than one. It also meant sacrifices. Beatrice left for work early in the morning, leaving Thai to get himself to school. Oftentimes he just stayed home.

Still, Beatrice always believed in her son. Life could be hard, but he was strong.

Standing at Lafayette and Bedford, Beatrice holds a sign she made: “Hey Mr Rager,” in big green letters, underscored by three lightning bolts.

The sign refers to Rage & Release, the cannabis-centred lifestyle community Thai founded in 2017. The group meets several times a month to meditate, do breath work, share meals, and run the streets of Brooklyn, often along the same stretch of road where Beatrice is now waiting. Thai says Beatrice was furious the first time she caught him with weed. He insisted she had nothing to worry about.

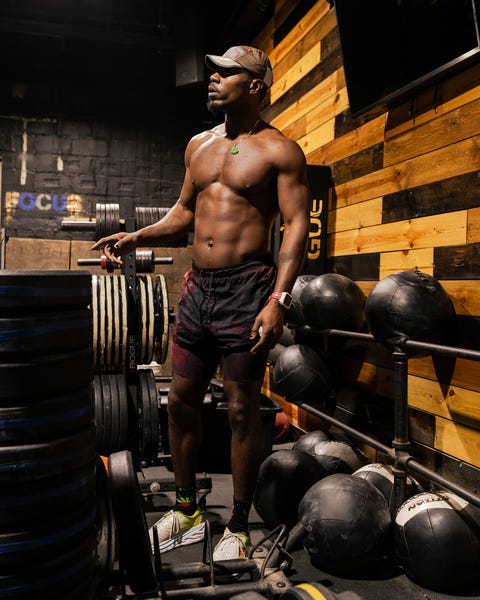

Beatrice waves her sign and holds her phone in her other hand, ready to take a photo the instant Thai runs by. The moment is significant. In his late teens and early 20s, Thai could have easily landed in prison or been killed. Instead, at the age of 30, he’s the literal face of the 2021 New York City Marathon, featured in its marketing banners, social media posts, and commercials.

Starring in a major ad campaign like this one isn’t the kind of influence that motivates Thai. His focus is more intimate. Friends call him the “consummate vibe curator,” and with Rage & Release he has created space for a community to coalesce around a common interest in running and using cannabis not to party or to zone out, rather to be present and talk about things like physical and mental health.

But this is more than just a story about running and weed. It’s about a mother and a son, and the memory of a father who never had the chance to be a dad. It’s about creating something new out of the material that’s all around you, simply by recognising a need and forming a community. It’s about getting lost and finding your way, and doing it on your own terms against the odds. It’s about resilience.

Thai and his friend wanted to shoot some hoops, but they didn’t have a ball. They were on the courts near the Unity Plaza Houses. Thai spent his childhood shuttling from one Brooklyn housing project to another: a few months in Flatbush, a year in Bed-Stuy, another in East New York. He knows he was in East New York on this particular day; he was living on Williams Avenue at the time, “one of the most murderous blocks in Brooklyn,” he says. “There was a field not too far away where they’d dump the bodies.”

He was 7 years old, already taller than the other boys. He and his friend went inside to get a ball. Down a narrow hallway, with institutional paint and linoleum flooring, they reached his friend’s apartment. Inside, the bathroom door was open; the boy’s father was on the toilet, a thick rubber tourniquet strapped around his bicep, a syringe plunged into a bulging vein in his forearm. They found a ball and went back outside.

Beatrice may or may not have known where Thai was. “It was just, like, I know my mum loves me and my family loves me, but there wasn’t too much engagement,” he says. “I wasn’t like the kids sent to karate school.”

For Thai, family was an assemblage of cousins, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Thai’s father, Henry, did a lot of things. “He was a hustler,” says Thai. “He cut hair, fixed cars, was a great student and athlete. He did what he could for his family, including drug dealing, but he was no kingpin.” It was the early ’90s, the height of the crack epidemic, and from time to time Henry and a friend would buy bulk quantities of the drug and drive to Georgia, or Virginia, or Ohio. They’d spend a few days selling their supply before returning to Brooklyn to re-up. They were still teenagers. In 1993, a store owner in North Carolina mistook Henry for the friend, “who was notorious for robbin’ shit,” Thai says. “They both 195cm, dark skin, braids.” The store owner shot Henry in the heart. He died instantly.

Thai has no memories of Henry and knows only that he had African and Native American ancestors. His mother’s family is from Guyana, a country with a patchwork of East Indian, African, South American, and European cultures.

Thai learned to take care of himself; he had no choice. From age 7, he was taking Greyhounds alone upstate to Ithaca to visit his uncle. “I always been comfortable just moving around by myself,” he says, “moving forward in my life.”

By age 10, Thai decided he’d had enough of the city. On September 11, 2001, he was at school in Brooklyn when two planes flew into the World Trade Centre. His teacher wheeled a television into the classroom and turned on the news. Thai sat at his desk and watched the billows of smoke, the charred bits of office paper floating down like confetti, the streams of people coming over the Brooklyn Bridge covered in ash. “I was like, man, I gotta get up out of here,” he says.

Beatrice’s sister, Kim, had recently moved to Greenwood Lake, a tiny hamlet about 80 kilometres north of the city, and Thai knew she had an extra room. He called her on the phone: “Hey auntie, can I come live with you?”

And so, a Black kid from East Brooklyn found himself in white suburbia. Greenwood Lake was serene, but dull. “You know the suburbs. Either you’re doing sports or you’re doing drugs or you’re doing both,” Thai says. By middle school, most of Thai’s friends had discovered cocaine, then opioids, and eventually heroin.

Thai didn’t mess with the coke or the pills or the H. Not after what he’d seen in the projects. “Heroin fucked everybody up so bad, dude,” he says. But he felt isolated; he needed something. He started running around the town lake, and eventually discovered nearby Harriman State Park, a 47,500-acre wooded preserve with lakeside beaches and kilometres and kilometres of trails.

“Running through the woods changed my perspective immediately,” says Thai, who is 193cm and moves with the poise of a dancer. “The nature, the fresh air, the rocks, just like, you know, dipping and diving over roots and just being immersed in nothing else.”

Thai liked that he could run alone; he liked being in motion. He didn’t see himself as a runner, though. His future was in basketball. He idolised Reggie Miller and Ray Allen, two of the top scorers in NBA history, and he knew he had to run if wanted to be great. “Reggie Miller always said if you can outrun your opponents, you can always score,” he says. “Same thing with Ray Allen. So I was like, I want to be like those guys.”

Thai made junior varsity in seventh grade, which allowed him to play on the high school team. He became friends with a centre named George, one of the few Black kids in the area. Thai knew George smoked weed, so one day he hit him up.

It was a hazy, beautiful spring day. “You had the trees, fresh air, the lake was right there. Regular suburban shit, but the vibe was so pleasant,” Thai says of that first experience smoking cannabis. They shot some hoops and went to George’s house; George’s family had everything. “You go to their crib, there’s chess, there’s Scrabble, there’s drums,” Thai says. “You didn’t just go to George’s house to smoke; you smoked and you were productive, you did something.”

“RUNNING THROUGH THE WOODS CHANGED MY PERSPECTIVE,” SAYS THAI. “THE NATURE, THE FRESH AIR, THE ROCKS, JUST BEING IMMERSED IN NOTHING ELSE.”

By eighth grade, Thai believed he was good enough at basketball to go pro. The season was still a couple of months away, so to get into shape he decided to do cross-country. One September afternoon, just before the bus departed for the first race of the year, Thai ducked behind the school to smoke a J. Nicely toasted, he hopped on the bus, joked with his teammates, and arrived at the course.

The day was warm, the leaves just starting to turn, the rolling hills of the Hudson Valley cutting a sharp profile against the pristine blue sky. Thai did a few drills, strided out, and toed the line.

At the gun, he flew across the open field, his spikes churning up clumps of dirt, and assumed the lead. For the next five kilometers, not one runner passed him. It was just him, his breath, his rhythm. He won the race, he says, in 17:02. “I was like, yo, this is the illest thing ever,” he says, his eyes sparkling at the memory. “And I was like, I don’t think I ever want to run sober again.”

Cannabinoids, with the exception of CBD, have been on the World Anti-Doping Agency’s banned substances list since 1999, along with EPO, steroids, and cocaine, among countless other substances too obscure to mention. Margaret Haney, Ph.D., a professor of neurobiology at Columbia University Medical Center, where she also directs the Cannabis Research Laboratory, has described the evidence that WADA provides to justify the ban as “extraordinarily weak.” It’s anecdotal at best and moralistic at worst, and none of it supports the theory that cannabis improves performance. A 2011 paper from WADA claims that cannabis slows reaction times, decreases coordination, and impairs psychomotor activity—the same reasons the agency uses to justify the ban, as cannabis may be “harmful” to athletes.

This past summer, the issue gained international attention when Sha’Carri Richardson was given a 30-day suspension following a positive test for THC at the U.S. Olympic Trials, where she had won the 100m in 10.86 seconds. It cost her the chance to compete at the Tokyo Olympics, eliciting a cacophony of support and derision from the public.

In September 2021, WADA announced that it would review its ban on cannabinoids. In doing so, the governing body will have to define what “performance enhancing” even means. Yes, cannabis might make an athlete feel good, but that’s not the same thing as “performance-enhancing” as we typically understand the term.

In 2019, the University of Colorado published a study of 605 athletes who use cannabis; 80 percent of them reported that while they did not feel it improved their performance, it did increase their motivation and made exercise more enjoyable. If that makes cannabis a performance enhancer, in other words, then why not antianxiety and antidepressant medications—or, for that matter, a good night’s sleep—none of which are on WADA’s list?

Chris Barnicle is a former professional long-distance runner with a half marathon PR of 62 minutes. He began using cannabis in middle school; now 34, he says that having a little weed before a run makes him “feel like Superman. Not that I have so much speed, or that I’m flying, but that all the negative thoughts just sort of disappear.”

Barnicle equates cannabis to something else he consumes daily: coffee. “The caffeine will get my heart rate up, and the cannabis is going to mute all the doubt and turn that into positivity,” he says. Unlike many substances on WADA’s list, like HGH—which increases bone mass and boosts testosterone, which builds muscle—cannabis causes no physiological or biological changes in the body. But, Barnicle says, “it is going to enhance, for a certain person, that positivity, that vibe you need as an athlete to be unstoppable.”

Thai made the varsity basketball team in eighth grade. By his freshman year in high school, scouts had their eyes on him; his future as the next Reggie Miller was coming into focus. It was to be a dream come true, until it became a dream deferred, then a dream unraveled. Midway through his sophomore year, Thai’s mom decided he should move back to Brooklyn. The way Beatrice remembers it, Kim had a new boyfriend who didn’t want Thai around.

Cultural whiplash—again. After six years of learning to fit into a mostly white community, Thai had to relearn how to fit into a Black one. “When I come back to the hood, I got people telling me, you sound like a white dude,” he says. “You know what I’m sayin’?”

Thai sank into a depression. He quit playing ball. It was too hard to stand out in New York City and he didn’t have an established support system and connections like he did upstate. He kept running, but he didn’t know any other runners in Brooklyn. They were all way older or way whiter. Usually both. He started cutting class. Going from a small school where his teachers looked out for him, to one with enormous classes where Thai felt anonymous, was a “huge culture shock,” he says. “It was difficult for me to find my groove.” He started acting out. One day he and a friend stole cellphones from some kids after school. No real reason, he says.

He missed getting lost in thought on long runs through the woods. “It was, like, I got to figure out myself as a Black person and as a human being overall. Running helped… me feel like I had control over something.” Cannabis helped, too, he says. It made him more introspective. He began to think about his past, and how to square that with his aspirations for the future. “It’s really hard as young Black men and young Black women to find balance,” he says, “when you have to constantly think about all the struggles of your environment and then the traumas you grew up with.”

The relationship between cannabis and mental health is tough to pin down. The plant contains more than 100 cannabinoids, whose various combinations and concentrations can create a huge range of effects, and not all of them are psychotropic. This makes it impossible to analyze cannabis as a singular substance or to issue categorical truths about its use: Some studies suggest that it can be an effective treatment for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even opioid addiction, while others have hypothesized that it causes, or at least exacerbates, those very conditions. In 2019, Jonathan N. Stea, Ph.D., a psychologist specializing in addictive and psychiatric disorders, wrote a roundup of the current research for Scientific American, titled “Is Cannabis Good or Bad for Mental Health?” The answer, according to the literature, can be summarized as: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Thai started meditating. Sometimes he’d skip class and go to tai chi; there was a studio not far from his school, and it beckoned to his curious mind. At night he’d smoke some weed and run loops in Prospect Park, a 526-acre oasis in the middle of Brooklyn, where it was less likely he might run into trouble. He says he was stopped by the police often enough as it was, always for something he hadn’t done, always for fitting the profile: 193cm, 90kg, Black. He had to play it safe, especially if he was carrying weed.

New York has a long and largely untold history with cannabis. It was decriminalized in 1977, but that never meant it was legal; it simply meant that having a little weed wouldn’t result in jail time, at least not until the third offense. But you could still get arrested, and the arrests almost always fell along racial lines. NYPD statistics from 2020 show that Black and brown people represented 94 percent of all arrests for cannabis possession in New York City that year—never mind that whites use cannabis at roughly the same rates as other groups, according to ACLU data. Every time Thai was carrying a little weed, in other words, he was gambling with his future. “Once you have a record, things get hard,” he says.

New York legalised recreational cannabis for 21-and-older adults in March 2021, making it the 15th state in the country to do so. But the law has its limits: It’s still a crime to possess more than three ounces, and anything over eight ounces is a felony, punishable by up to four years in prison and a US$5,000 fine. The penalties get harsher as quantities increase, and are especially harsh for distribution.

To this day, Thai has no police record. Call it luck, or maybe providence. The security guard who caught Thai stealing phones warned him that if he didn’t leave the school that day, the authorities would press charges. Thai transferred to an alternative school in Queens. In his late teens, he started selling enough weed that he’d have been charged with a felony if he ever got caught. It was a way to make fast cash and to ensure that his own product was natural and clean. Synthetic weed was flooding the market at the time, sending people to emergency rooms, or into psychosis and seizures on the street. Natural cannabis wasn’t entirely safe, either. Thai says he regularly found plastic toys, fingernails, human hair, and dead animals in bricks of weed.

Dealing was never Thai’s sole hustle. At 18, he started going on model casting calls; before long he signed with an agency, booking jobs with Nike and Adidas, among others. He supplemented his income with catering and security gigs at VIP lounges, private parties, and galas. “VIP people always like beautiful people to look at,” he says. He worked at some of New York’s most exclusive clubs; sometimes he sold weed to their clientele. Still, he struggled to find a place to live. He crashed with friends or girlfriends, often in the same housing projects he grew up in.

One day in November 2012, just after Hurricane Sandy tore through New York City and left thousands homeless or unemployed, Thai set up a deal to sell a half pound to someone he didn’t know well. It was a crisp, clear afternoon. Thai met the guy on a side street in Crown Heights, just off Utica Avenue. The guy led Thai into a large prewar apartment building, the kind with multiple entrances, a maze of hallways and emergency exits.

Thai’s pulse was steady. Standard procedure. He’d been pushing weight for a few years, always as a middleman between a supplier and street dealers. He’d been in lots of empty hallways with strangers, exchanged many bundles of cash for weed. He rarely felt intimidated. He had 15cm, at least, on most other guys, and if he had to, he knew he could outrun just about anyone.

All of a sudden, “two other homies popped out of nowhere,” Thai says. One pressed the end of a handgun into Thai’s temple; the other patted him down. He was trapped. This time, running wasn’t an option. They took the weed and split. Street value: US$1,800.

Thai was angry, but not at those who’d robbed him. “I allowed somebody to have my life in their hands, and that’s… that made me truly uncomfortable,” he says. “I felt like I had humiliated my own self.” He resolved to pay his supplier back and to find a new path. He knew where this one might lead. He didn’t want to wind up like his father. And running, as always, was his rock. It was the “only way that I’ve been able to cope,” he says. It may have even saved his life.

Thai went full throttle with Nike. Soon he was in store windows, and after that, working at the Nike flagship store in Flatiron. “That’s where I met most of the running community,” he says.

Between modeling, catering, and security, Thai was making good money, and it was all legit. But he still didn’t have the paperwork to get a place. Most landlords in New York City require proof that an apartment applicant earns an annual salary 40 times the monthly rent, has a credit score of at least 700, and can provide multiple pay stubs proving steady, full-time employment. Thai had the income, but nothing else. “You don’t get taught financial literacy in the hood,” he says. Absent any of that, a guarantor—someone who cosigns on the lease—will suffice. Thai didn’t have that either.

Thai finally got an apartment with a friend in 2015, the year he turned 25. He’d landed a modelling gig with Nike that paid him US$10,000 for one week of work, enough to lay down two months’ rent plus double the security. It afforded him a bit of stability in an otherwise chaotic life. He began training for the New York City Marathon. He’d applied through the lottery but didn’t get in, so he bought a bib online and ran under someone else’s name. He says he finished the race in 2:50, a stunning time for someone of Thai’s size, but celebrations were short-lived. Not long after that race, Thai and his roommate had a falling out. He was back on the street.

Thai’s fitness took a hit. It’s hard to maintain a healthy diet, regular sleep patterns, and a consistent training regimen when you don’t have a place to live. But he still wanted to run his hometown marathon, and in 2016 he again applied through the lottery. Again, he didn’t get in. He bought another bib online, unaware that it was counterfeit and that dozens of others had bought one just like it. An official at the race start spotted Thai’s bib in the corral. He was banned from NYRR races for the next two years.

Thai didn’t need NYRR to run. But he did need a community, and he wasn’t finding it in the New York running scene as it existed. He knew he wasn’t alone.

Rage & Release started small. Just a few people at first, meeting up to run, meditate, and smoke some weed, not necessarily in that order. In its first couple of years, it was a side project for Thai, something he folded into his personal brand as a model. And though he knew he’d landed on something, he didn’t realize its potential. That changed in 2017, when he met Kenisha (Kenny) White.

Kenny had come to New York from Virginia two years prior for a three-day visit and never left. She met Thai through running, which she took up after she moved to the city. “I always used to say I’d only run if I was being chased,” she jokes.

Thai told her about Rage & Release, his vision for what it could become, and the people he wanted it to serve. Thai’s modeling and security work had introduced him to luxuries he’d never known growing up. For him, that was the core of the problem. “You have to focus on Black and brown communities, because wellness is totally out of reach for them,” he says.

Kenny had worked in brand activation for Zagat and as a program manager for The North Face. She had some ideas, and joined as cofounder. She built a website and created an Instagram account. They wrote a business plan and got serious about the future of Rage & Release. Thai’s side project was becoming a mission.

“YOU HAVE TO FOCUS ON BLACK AND BROWN COMMUNITIES BECAUSE WELLNESS IS TOTALLY OUT OF REACH FOR THEM,” THAI SAYS.

The vibe at a Rage run is chill. As the runners wait on street corners for lights to change, a few will take turns doing pullups on a walk sign. Thai might do a set and then drop to the pavement for some curbside pushups. Along the way, he’ll retrieve a long, fat joint from behind his ear, and flick a lighter. He’ll take a pull and resume running.

After an easy jaunt through Bed-Stuy, or Clinton Hill, or to Williamsburg and back, the group will convene in a vacant lot in Crown Heights next to Dean CrossFit. Rows of exercise mats line the rectangular space, a makeshift urban sanctuary nestled into a strip of auto-repair shops and repurposed garages. Thai will lead a program of post-run stretching, deep breathing, and meditation before sharing the rest of the joint with whoever wants to partake.

Leadership comes naturally to Thai. Ronald Peet, a NYC-based actor who started running with Rage & Release in June 2020, says he was “completely mesmerized” the first time he saw Thai. “He looked like a superhero and had the energy of a teddy bear,” he says.

As central as running is to Rage & Release’s backstory, Thai says it’s only a piece of their grand plan. They want to open a space in central Brooklyn, not far from Dean CrossFit, to be accessible to lower-income neighborhoods like East New York and Brownsville. They’ve begun curating art exhibitions, holding meditation circles, and developing programs around cannabis and wellness education. They’ve even organized dinner parties with private chefs that pair two very different cuisines in the same meal. They call the dinners Bang Bangs, and like many things in Thai’s life, he says they were inspired by the multicultural stew of Guyana.

At one Bang Bang last October, two Brooklyn-based chefs, Toya Henry and Rachel Laryea, prepared a six-course meal combining elements of Caribbean and Southeast Asian cooking, with dishes like turnip carpaccio and pickled breadfruit. Thai says he hopes the Bang Bangs will inspire deeper, more intentional engagement with food—not unlike his approach to cannabis. “Consumption is what humans do: consume, consume, consume, consume,” he says. “But we get so caught up in the mainstream that we don’t even know what’s good for us anymore.”

None of the dishes at the October Bang Bang was infused with cannabis, though it’s usually present at Rage & Release events, including Bang Bangs. Thomas Llaurado, who’s gone on more than 20 Rage runs since he moved to Brooklyn in 2019, describes Thai as “the consummate vibe curator,” and a big part of that is giving everyone the space to shape the experience as they wish. “Although cannabis is always welcomed,” Llaurado says, “it’s never pushed on anybody.”

The day started out gray. But by noon it had turned into one of those perfect October afternoons, golden, 60 degrees in the sun. Thai had invited me over to his place for tea. He lives now in a tidy five-bedroom apartment in Bed-Stuy with Kenny, his cousin CJ, his Aunt Boo (Henry’s sister), and two Shih Tzus. “I was blessed enough that everyone in our house now has the right paperwork and credit scores,” he says.

We’d made plans to go for a run. But first, a cup of tea and a little sativa—a strain of cannabis known for its energizing, uplifting effects: perfect for a pre-cypher, as Thai calls it. As I sipped the warm herbal concoction he’d prepared, we passed a joint back and forth and talked about his sneaker collection, the provenance of the weed we were smoking (a small organic farm upstate), and some of the research I’d done for this article. I told him about Chris Barnicle’s belief in cannabis’s ability to mute self-doubt, and Thai nodded. I also said that while I’d used cannabis myself since high school and started running at 23, I’d never once run high. He nodded again and smiled. He’d heard that one before.

We gathered our things and went downstairs. Thai put on a playlist of ’70s Nigerian funk and ’90s hip hop, channeled through a small speaker in his backpack. I asked him what pace he was looking to do. “Seeing as I’m just waking up, 4:40s,” he said. “Sounds good,” I replied. And with that, we set off through the streets of Brooklyn.

Immediately, my 46-year-old body felt lighter than it normally does at the start of a run. We covered the first 1600m in just under 8 flat, then 6:40, then 6:13. We didn’t talk about speeding up; it happened organically. I fell into lockstep with Thai’s cadence as he guided us, wordlessly, through the leafy blocks of Clinton Hill and Fort Greene, over the Manhattan Bridge, and into Lower Manhattan. And while it didn’t feel easier than any other run at the same pace, it clicked differently. I felt in perfect harmony with myself, with Thai, with the city. As the route became more congested, with people and cars and food delivery bikes, we seemed to simply float through it all.

“THE ‘POWERFUL BLACK MAN’ IS TRENDY RIGHT NOW,” HE SAID. “I KNOW I’M A TOKEN.”

On the train back to Brooklyn, we talked about organisations like NYRR trying to capitalise on Thai’s image. He said he’s happy to play the game—“I need to eat too,” he said—but he’s not naive. “The ‘powerful Black man’ is trendy right now,” he said. “I know I’m a token.”

We talked about declarations of “supporting the community” that have become the fashion in corporate messaging today, about how a lot of it is just opportunistic woke-washing. He told me about a situation where a major brand had asked to partner with Rage & Release on an event and then reneged at the last minute, leaving Thai to cover the US$9,500 fee for the space alone. There was no way he could afford it. He didn’t seem angry; he didn’t even seem surprised. He looked down the length of the train car, shrugged, and looked back at me: “They fucked us, bro.”

Two steps forward, one step back. Story of a life.

Days later, Thai texted me an update: The company was going to honor its arrangement after all. “They realized it would look bad on their end,” he wrote.

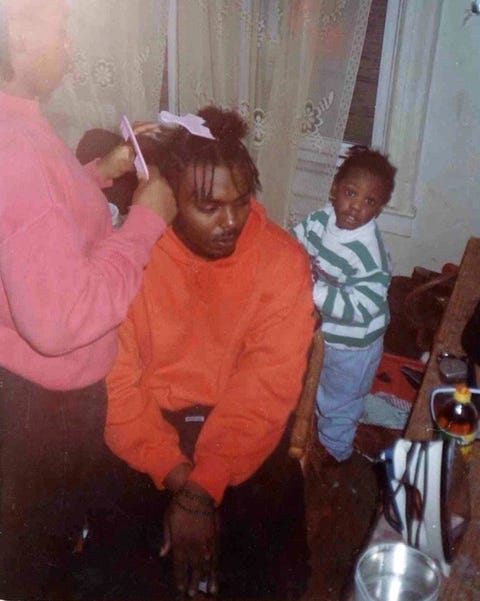

Beatrice Richards stands at the edge of the sidewalk and peers down Lafayette Avenue. A smattering of runners morphs into dozens, then hundreds, then thousands. She is looking for just one. I’d come to watch the marathon with Kenny; meeting Beatrice is a welcome surprise. Thai inherited her eyes, honest and kind. Her smile, warm and broad. Her demeanor, calm and direct. I tell Beatrice that I can see the resemblance and she laughs. “You should see his father.”

Within seconds she’s pulled up a photo on her phone, taken when Thai was just 2 years old, not long before Henry was killed. In it, Henry sits on a kitchen chair as Beatrice braids his hair; he wears a bright orange sweatshirt, his eyes cast downward. Thai stands behind him wearing a striped shirt, looking straight at the camera, his eyes wide. It’s one of those quotidian moments that seem to have been captured only on film, before cellphones allowed us to curate our lives in real time. It is not, formally speaking, a good photograph. Time has turned it into a perfect one.

Beatrice is right: Thai looks like Henry. He has his cheekbones, his shoulders, his athletic build. He has Henry’s drive, too, she tells me. “Henry was a go-getter,” she says. He’d been selling crack for only about six months when he was shot in North Carolina. He was just trying to feed his family, she says. It was just a temporary thing.

Thai inherited Henry’s trusting nature, too, she says; she hopes it doesn’t hurt him. Henry’s friend wasn’t really his friend, she says. “He killed Henry. It was a setup.” She says the friend swapped his jacket for Henry’s to confuse the store owner. I ask why he would do that. “He was jealous of Henry,” Beatrice answers, “of what he had. I don’t know.”

Beatrice isn’t surprised that Thai is such a talented runner; she ran track herself. Nor is she surprised by what he’s doing with Rage & Release. Ambition runs in the family. All those years that Thai was on his own, Beatrice was busy growing up too. She put herself through school when Thai was little, earning a business degree at Kingsborough Community College and later taking courses at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. After working the past 20 years at Rikers Island, New York City’s notoriously dangerous jail, she’s about to retire as a captain in the corrections department. She says she always knew, even when she caught Thai with weed, that he wouldn’t land there. He’s always known his limits, she says. “He’s always been smart.”

As for Rage, “I love it,” she says. “I just hope he can get the word out, get some more investment.” I ask her if she knows I’m writing this article. She doesn’t. Tashawn’s too modest, she says, using the name she gave him at birth. He hasn’t told her.

Suddenly Thai flies past mere inches from the curb. He knew Beatrice and Kenny would be there and he made sure to get as close as possible. Beatrice whoops as she holds her handmade sign high in the air and hurries to snap a photo. Thai pumps his right fist, gives Kenny a high-five with his left, and cruises on to Bedford Avenue.

The sub-3 pace group follows close behind, not that Thai is paying attention. He doesn’t need a pace group. He has his crew, his rhythm. And even if he didn’t, even if he fell off his pace, even if he pulled a cramp and had to walk, he isn’t stressing it. He’ll ultimately finish in 3:08, exactly what he’d predicted. Later that day, Thai posts a photo on Instagram of himself smoking a joint, wearing his post-race poncho and donning his medal, with the caption: “The stigma around cannabis as we know is changing yearly due to science and mf’s like me who showcase anything is possible with the right lifestyle. It’s not what you do, it’s how you do it.”

On Tuesday after the race, around 30 people gather outside Dean CrossFit. They hug and catch up and congratulate each other on their recent marathons. Thai lights a small bundle of sage and welcomes the group into the vacant lot next door. He says a blessing for everyone who ran New York and leads the group in some breath work and warm-up exercises. Then he tells them the route, an easy 5-kilometre loop up Bedford Avenue and back via Fort Greene, walks outside, and lights a J. And with that, nicely toasted, he starts to run.