Inside the little-known race in 1967 that helped spark equality in women’s distance running.

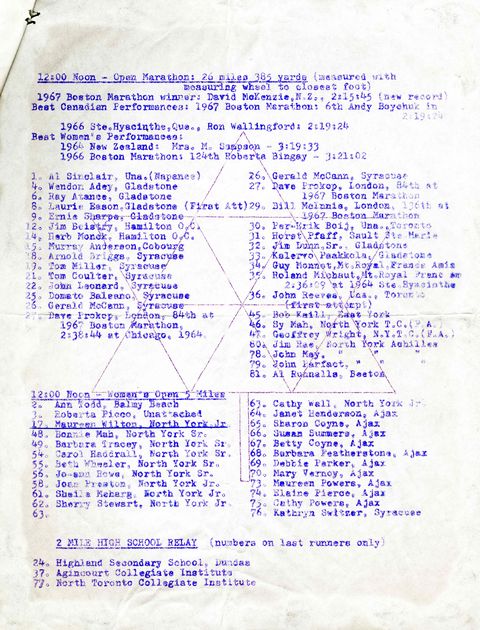

On May 6, 1967, Maureen Wilton, a 13-year-old girl from a suburb of Toronto, Canada, attempted to break the women’s marathon world record of 3:19 at a small race a few km from her home. Under the guidance of her track coach, Sy Mah, she had already become one of Canada’s best female distance runners in races up to Eight km—the farthest distance race organisers would allow women to run. Seeing Wilton’s potential to break barriers in the marathon, Mah battled the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union to allow her to race 42 km The organisation refused to officially recognise her as a competitor. Her name was left off the marathon section of the official program. Still, she lined up on a dusty road that Saturday to complete five laps of a roughly 8 km course with 28 men and one other woman—Kathrine Switzer, who joined the race two weeks after her own iconic Boston Marathon finish. The following is an excerpt from the book Mighty Moe: The True Story Of a 13-Year-Old Women’s Revolutionary, out now.

Maureen looked small standing in the grass on the side of the cracked asphalt road, like a loitering kid who’d snuck into an event for adults. Newspapers regularly commented on her size when they reported on her races around Canada and the United States.

They called her “little” and “tiny.” She was—even At thirteen—still a petite four foot eight and 36 kg. But if size is just a comparison from one thing to another, then what the reporters observed when Maureen raced against girls and boys nearly her own age was nothing compared to the whir of activity around her now.

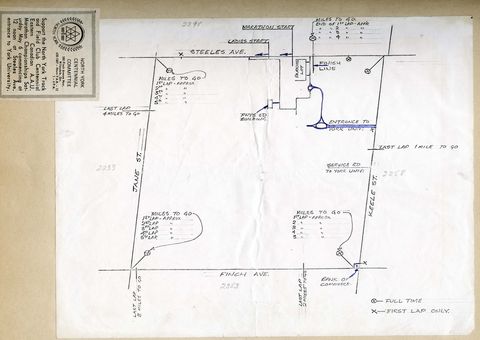

Here on Steeles Avenue, just north of the new brick buildings at York University, ten minutes from home, Maureen had never looked smaller. Twenty-eight grown men stretched and jogged and chatted along the road. They looked like billowing trees in a storm. Maureen stood at the edge of the motion, reluctant to enter the fray.

“You have to go now,” her mother, Margaret, pleaded firmly. “The race is about to start.”

Nerves burbled in Maureen’s stomach. Not for the race—the race she could handle. But for the idea of approaching these men. She knew some of them; they ran with her coach, Sy, on weeknights at the track. The ones she didn’t know looked friendly enough in their cotton T-shirts and scrunched-down socks. But she worried what they would think when she approached, in her maroon shorts and singlet—a uniform that all but announced her intention to run with them.

What will they say? Maureen wondered.

“You need to go. Now,” her mom said. “They are about to start.”

Maureen pulled off her baggy sweatpants—the same ones she hated people to see her wear on training runs—and trudged toward the crowd. As the men continued to stretch and jostle and crack jokes, their lanky limbs whirled as if caught by a gust of wind peeling down the road. They were warmed up.

As she shuffled closer to them, Maureen felt like she’d entered a restricted room during an important meeting. Like when you accidentally open the wrong door and everyone turns their head toward you and the whole space falls dead silent. She walked right next to the men, the top of her brown hair barely reaching their torsos. They parted ways to let her through. Some of them looked confused.

Maybe this girl is mistaken? Shouldn’t she be with the other girls?

The other girls were off to the side. There were a few dozen of them, waiting for their own race—a five-mile women’s open that would start once the main event kicked off: The Eastern Centennial Canadian Marathon Championships.

“Runners, take your mark,” a man yelled from the side of the road. Sy approached and took his spot next to Maureen. He was racing as well. He wore shorts and a T-shirt, His usual black glasses perched on his nose.

“Get set.”

The group took a collective breath. Maureen’s muscles clenched. She looked straight ahead. To the left, she could see the cluster of brick buildings. To the right, unkempt grass and farmland. The road wasn’t closed, but even at 11:59 a.m. on a Saturday, there were no cars. The men dissolved in her peripheral vision. This felt familiar—the quiet tension in the moments before the pistol fires.

Crack!

Twenty-eight men, a young woman from Syracuse University, and a thirteen-year-old girl from just up the road began to amble west. Only one of them was trying to break a world record.

This pace is soooooo slow, Maureen thought after the first mile.

The easy effort felt like a warm-up. She settled into a running rhythm near a group of men at the middle of the pack. Sy ran next to her. He expected to stay by her side through the whole race, helping her keep on track. This was Maureen’s first marathon. But it was Sy’s first marathon, too. He also was confident he could keep up because, one mile in, this speed felt easy to him.

Seven minutes and thirty seconds.

She needed to hit this pace perfectly at each mile marker. Like a metronome.

That’s a fast clip for a beginner. But Maureen felt, gliding on muscular legs that had completed thousands of miles in training, like she could do this forever.

It was a strange feeling for her. In typical races, the tension doesn’t cease after the starting gun goes off. Your legs fire off the line. You can’t relax, your muscles burn. You begin to breathe hard. You can’t speak or smile or wave. Maureen was doing all three in the first miles. She’d never felt so wistful and at ease during a competition before. She was just happy to be away from the starting line, away from the tension. She was doing what she loved to do. She was running. Albeit running really, really slowly. For her, that is.

Seven minutes and thirty seconds. Seven minutes and thirty seconds.

That’s what she kept thinking, repeating the time in her mind as she jaunted through the first mile, then the second, then the third, like clockwork. Except Maureen didn’t need a clock. She didn’t need someone at each mile marker to tell her how fast her pace was. She could feel it, within a few steps one way or the other.

In practice, Sy could tell her to run 400 meters in seventy-five seconds. She usually missed that time by less than a second. She knew that with the smallest adjustment in how hard her foot struck the ground or how quickly the breath sucked into her lungs and blew out her nose, she could change her pace.

Mile four: seven minutes and thirty seconds.

Mile five: seven minutes and thirty seconds.

This was easy. It was fun. Maureen was next to her coach on a deserted two-lane road just a short distance from her house. It was a weekend day in May and she was going to the lake cottage soon.

“Gee,” she said to the crowd standing near the refreshment stand at the end of the first lap. “This is great!”

The pressure peeled away like an onion. This felt like no race she’d ever run before. There weren’t any girls to chase after, except the one she didn’t know (Kathrine fell far behind Maureen from the start). No burning, aching lungs, desperately trying to motor her to a finish line.

At the end of each of the 5-mile laps, she stopped and crouched behind a canvas tent staked into the ground. It served as a little bathroom for runners. Maureen thought this was funny, that in the middle of a race, when nature came knocking, she had time to pee and was still hitting her goal pace each mile.

The distance floated by with cheers from friends and parents. This felt so easy, Maureen began to wonder what the big deal was. Why did she have to feel so uncomfortable at the start line of this race? Why did she have to feel like she didn’t belong? Why did anyone want to stop her from running a marathon when it felt this effortless and this fun?

Complete a few more miles, and Maureen Wilton would be the first woman in Canada to finish a marathon. Continue at the current pace, and she’d be the fastest woman in the world to ever do it. History is funny. Those who make it often don’t know they’re making it in the moment. Maureen certainly didn’t.