You can’t leave it to the naked eye to make a call as close as the 100-meter final.

BY BRIAN DALEK PUBLISHED: AUG 05, 2024

Noah Lyles backed up his words and became the world’s fastest man by winning the men’s 100-metre final Sunday night in Paris. But as he gazed up at the Jumbotron high atop Stade de France, in the turn just past the finish line, with Kishane Thompson of Jamaica, he admitted afterward that he thought he was bested.

“When we both crossed the line, he came to me and said, ‘Hey, man, I think you got it,’” Thompson said after the race. “I was like, well, I’m not even sure because it was that close.”

After what felt like an eternity of waiting for a result, Lyles’s name popped up on the screen as the winner, surprising even the 27-year-old sprint star.

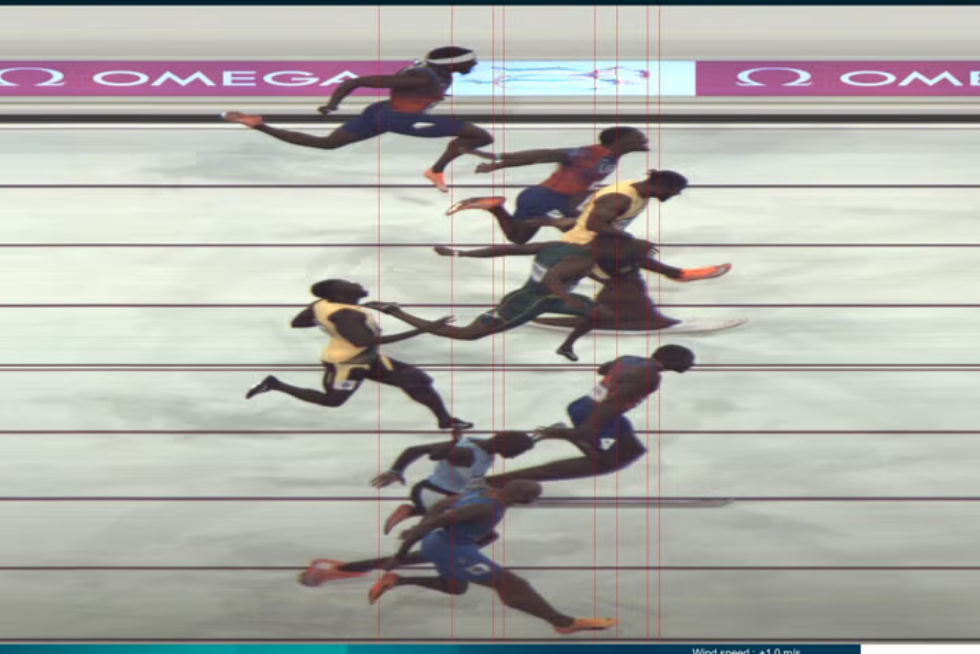

It came down to just .005 seconds between the two—9.784 for Lyles to Thompson’s 9.789. Depending on your view in the stadium or how closely you watched it on television, one could make a solid case that Thompson or even bronze medalist Fred Kerley (9.81) was the victor—if you look close, isn’t Kerley’s right spike ahead of everything else in the frame?

It’s the definition of a photo finish.

According to statistics provided by the official timekeeper of the Olympics, Omega, Lyles had a reaction time of 0.178 seconds out of the blocks—tied with the slowest reaction time of the field. But it was how Lyles reacted later in the race that got him the win. He reached a peak speed of 43.60 km/h just past 65-meter mark. It was the highest top speed of the race among all competitors, representatives from Omega confirmed to Runner’s World on Monday.

And when others in the field started to slow toward the end, Lyles managed to maintain his speed for the final 34.85 meters. His 9.79 is a new personal best.

But it wasn’t just the speed that won it for Lyles. It also came down to how Lyles crossed the finish line. For a look at how a photo finish is called in a race of this magnitude, we spoke with Alain Zobrist, the official timekeeper of the Olympics and CEO of Omega.

How do you determine the winner in a photo finish?

For timekeepers and judges of events like track and field, it’s a pretty simple answer: the front of the chest determines who gets the nod in a photo finish. Not the head, and not the lower body. If you look at the photo below, you can clearly see Lyles, third from the bottom, has his torso ahead of everyone else’s.

The result of a photo finish shot like you see at the top of this article comes from four critical cameras looking at the finish line. “Every camera takes a 40,000 pictures per second of the finish line,” says Zobrist, “allowing us to have a clear understanding of what’s happening on the finish line, and these are pictures that are taken are stitched together next to each other and we can produce a photo finish image.”

The main and the first backup camera are positioned near the timing room in the stadium at the top, focused on the finish line. The second backup camera is slightly lower to have an a different angle, and the infield camera from the other side provides a fourth alternative angle right next to the finish line.

How quickly can you make that decision with a race like last night’s?

Zobrist says that when getting the official time for any athlete in a typical race, it takes about 3 seconds to have an official time and place. For a photo finish race like Sunday’s he guessed it took the official timekeepers and judges on site 10 seconds to determine the first two positions, so about 5 seconds each for Lyles and Thompson.

“It’s okay considering it’s 100-meter final of the Olympics and the race was extremely close,” Zobrist says.

A time-lapsed look at the entire 100-meter-final. Noah Lyles is in lane 7 (third from the left) and Kishane Thompson is in lane 4.

Is there a weird pressure to get the results out quickly?

Zobrist has been working in the Olympics since 2006, so he has been through this type of situation before. Despite our need for instant gratification as a viewer, sometimes it’s about making sure the call is always accurate.

“Speed is irrelevant. It is the most important to have the right result out,” Zobrist says.

It’s in the blank space between crossing the finish line and the anticipation for the result that leads viewers astray in a race that close. While it may have felt like a lifetime to Lyles, Thompson, and the public watching in the stadium and on televisions around the world, this was a pretty quick and painless decision by everyone involved.

“I think that the difficult thing to understand is that it’s not a wide-angle picture, right?” Zobrist says. “It’s a very narrow picture of many of them stitched together to understand what is happening on the single point on the finish line through time.”

Are other sports tougher when it comes to photo finishes?

Less than 12 hours later, another photo finish was in store in the mixed relay triathlon, where Laura Lindemann of Germany anchored her team to an epic victory at Pont Alexandre III on Monday, besting the teams from the USA and Great Britain. The photo finish was actually more needed to determine silver and bronze.

Not many other sports have such nail-biting finishes, though Zobrist thinks track cycling is often more difficult than anything.

“Just because of the velocity of the sport, there is no chance you can see with the naked eye who crossed first,” Zobrist says.

Lyles isn’t done in Paris. He’ll be lining up as a favorite in the men’s 200 meters, starting on Monday. And he should be selected for the 4×100-meter relay team as well.

He’s probably hoping those final races aren’t as marginally close as his thrilling 100-meter sprint for gold.